Adaptations of an original beloved manga or other ‘sacred’ properties, can often put an audience’s back up. And since 2014, the film’s production has been plagued by damning accusations of Hollywood whitewashing and of course, the age-old argument: What’s wrong with the original? With 2017’s Ghost in the Shell, this reviewer can regretfully report, that Hollywood officially has a fault with their imagination.

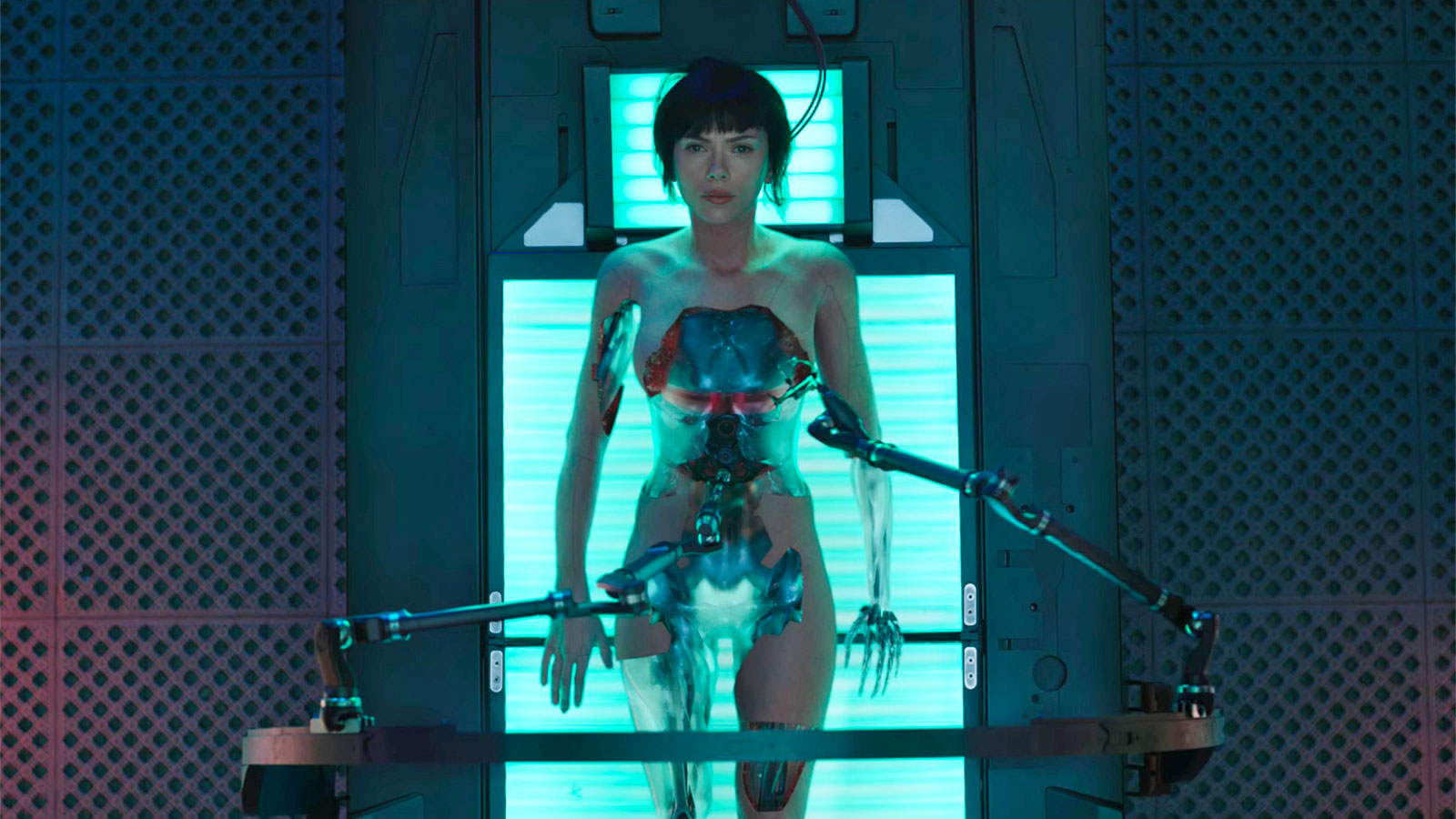

In 2029, the world as we know it, has been forever altered by the rapid evolution in technology. A vast electronic network now connects every human being on the planet. Whilst cybernetic enhancements replace antiquated practices, such as going under the knife. Instead, limbs, eyes (and often entire bodies) can be replaced with sleek, robotic alternatives, named “shells” – enabling it’s user to be endowed with superhuman abilities. But with the perpetual development of technology, cyberterrorists continue to thwart man’s progress at every turn. Employed by the government, Section 9 – an elite task force – is the only line of defence against a faceless enemy. But upon the emergence of a murderous cyber-criminal named Kuze (Michael Pitt), the trust between Section 9’s cyber enhanced leader, Major (Scarlett Johansson), her mysterious superiors and Hanka Robotics, is hazardously strained.

On November 13th 2016, the first full trailer for Ghost In The Shell debuted to the world. In addition to promising the acting presence of Scarlett Johansson, the trailer promised a society dominated by a killer cyberpunk/Blade Runner aesthetic and a slew of fascinating gadgets/robots – including some painstakingly designed and equally terrifying Geishas… Alas, the intrigue ends there. For Ghost In The Shell is – apart from the concepts lazily extracted from the original manga – devoid of a heart, amongst its intricately wired and sleek body. With every opportunity to consider what it is to be human or to debate the alarmingly inadvisable self-improvement of the human body (via robotics), writers Jamie Moss, William Wheeler and Ehren Kruger instead opt out for a series of albeit slickly photographed, but ultimately lacklustre action sequences, punctuated by clichéd plot machinations and uninspired dialogue. Worse still, the concept of ‘character’ is literally reduced to a protagonist, antagonist, mentor and the type of cannon fodder that barely possesses a name – you know, the characters who state a name so quickly and infrequently, that the writers are practically admitting how pointless they really are? And even in their frequent slow motion glory, characters such as Pilou Asbæk’s Batou rely on their (undeniable) ‘cool’, over development. And if that wasn’t enough, the talent of legendary performers such as Juliette Binoche and an ultra-cool Takeshi Kitano is criminally wasted.

Yet, one of the film’s few scenes void of any noise, remains it’s most impactful. As Major desperately clings to her formerly human qualities, she meets with what one can assume, is a prostitute. Sexual activity does not occur between them, yet Major lightly presses her hand against her cheek. In a relatively short moment, all of the pain and confusion felt by Major is conveyed simply, yet effectively, through Johansson’s unique gift of facial expression. An outsider, Major is frighteningly similar to the ruthless, yet poignantly inquisitive Female of Jonathan Glazer’s Under The Skin. Potential double bill?

If you’re listening Hollywood, know this: the merging of intellectual discussion and awe-inspiring spectacle is entirely possible – it has been achieved. Trust your mainstream audiences to be able to tap into challenging motifs – they are willing. In the unfortunate case of Ghost In The Shell, all that remains which is worth praising (at the end of its surprisingly arduous 107 minute running time) is it’s stylistic beauty, a delightfully moody score from Clint Mansell, and Michael Pitt’s commanding, unsettling android. For Ghost In The Shell to possess the emotional impact it so desperately longs for, it required purpose. And perhaps they were “so preoccupied with whether or not they could, that they didn’t stop to think if they should.” But that isn’t what filmmaking is about.

Ghost in the Shell is out in cinemas now!